Program Notes: Stern Conducts Tchaikovsky

Jean Sibelius, The Oceanides, Op. 73

Few composers are as closely identified with their homeland as Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. Finland had long been subject to Swedish rule before being ceded to Russia in the 19th century. Thus, it should not be surprising that Sibelius grew up in a Swedish-speaking family and didn’t learn Finnish until his later school years. It was at that point he discovered the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, which would provide him with tremendous compositional inspiration over the years. At the age of 14, he began studying violin with a local bandmaster but subsequently entered the University of Helsinki to study law. Following a long tradition of composers abandoning legal studies in favor of music, Sibelius launched headlong into serious violin studies, spending two years in the cosmopolitan atmosphere of Berlin and Vienna. Influenced greatly by the music of Beethoven, Wagner, Richard Strauss and Bruckner, he returned to Finland in 1891 and began to enjoy success with early compositions. He reluctantly gave up his aspiration to be a concert violinist, having started his studies so late.

In 1892, Sibelius and Aino Järnefelt married; the couple was together 65 years despite a number of relationship difficulties. They had six daughters, one of whom died from typhoid as a toddler. Despite his rising star, Sibelius did not lead a placid life, often going on alcoholic binges and spending beyond his means as he disappeared for days on end. Teaching duties at the Helsinki Music Institute (now the Sibelius Academy) limited his time for composing so he welcomed a grant in 1898 that allowed him to focus on composition. His First Symphony premiered in 1899, its overt patriotic spirit stoking nationalist sentiment and making Sibelius a Finnish hero in the midst of Russian subjugation. Other works such as Finlandia and The Swan of Tuonela burnished his reputation among the Finnish people and began enhancing his status internationally.

In 1904, the Sibeliuses built a new home near Lake Tuusula, north of Helsinki, which would be their refuge for the rest of their lives. Sibelius began facing a number of health concerns, including surgery for throat cancer. An increasingly pronounced hand tremor interfered with composition and a spate of headaches was also problematic. He became convinced of his early death but the scare also served to renew his musical endeavors and several major works resulted.

By the 1920s, Sibelius was composing relatively little music; his Seventh Symphony (1924), incidental music for The Tempest (1925), and Tapiola (1926) essentially served as final bookends on his career. During the last 30 years of his life, he enjoyed the countryside and many visitors but wrote nothing of consequence. He struggled for years composing an eighth symphony but according to various sources, he burned the manuscript and all drafts. He settled in to enjoy a lengthy retirement, dying at the age of 91.

The Oceanides tone poem (Aallottaret in Finnish, or Nymphs of the Waves or Spirits of the Waves) came about through a commission brokered by Horatio Parker, then Dean of the Yale School of Music, on behalf of Carl and Ellen Stoeckel, enthusiastic patrons of the arts. The Stoeckels hosted an annual music festival at their Connecticut estate and offered $1,000 for a symphonic work to be premiered at the 1914 Norfolk Music Festival. Sibelius eagerly accepted the commission in September 1913, thinking there was ample time to meet the April 1914 deadline despite a backlog of other music to be written. He finally began work on it during a January 1914 trip to Berlin but was dissatisfied with the results (two movements of the projected three-movement piece are extant) and returned home in February, anxious about the impending deadline. Taking a different approach and working diligently, Sibelius completed the tone poem in late March. Vacillating between German and Finnish titles (Rondeau der Wellen or Rondeau of the Waves, and Aallottaret), he mailed the score and parts — now known as the Yale version — to Parker. Only a few days later, he received an invitation to conduct the premiere as well as receive an honorary doctorate from Yale University along with an enhanced commission fee. Regardless of whether this change of circumstances prompted Sibelius to rethink the piece, he began wholesale revision of the work, including shifting the key from D-flat major to D major. His wife, Aino, described the process in her diary:

(14th May) The journey to America is approaching. Rondeau der Wellen is not yet completed. Feverish hurry. The journey has been scheduled for Saturday. The score is still unfinished. The copyist, Mr. Kauppi, lives with us and writes day and night. Yesterday we learnt that he has to leave already on Friday evening. It’s indescribable. It was a question of using every last hour. Besides, the whole practical side is completely unprepared. This can work only with Janne’s energy. Otherwise the journey would be completely out of question. (…)

Yesterday evening we couldn’t accomplish anything practical anymore, but then Janne forced himself to work with his great strength. There are still about twenty pages missing. We lit the lamps in the dining-room, the chandelier in the drawing room, it was a solemn moment. I did not dare to say anything. I just tried to create a pleasant environment. Then I went to bed and Janne stayed awake. All night long I kept hearing his steps, sometimes quiet playing. Towards morning he had moved upstairs. The copyist was awake in his own chamber. It is morning now. The tension continues, there are many things to be done today.

Later in May, Sibelius sailed for his first and only trip to the United States, still making adjustments in the tone poem on the voyage. Upon arrival, he was received as musical royalty, with high society receptions and grand accommodations. He conducted a stellar orchestra for the premiere on June 4, 1914, with musicians from New York and Boston. He observed:

Up till now I have never (…) conducted another orchestra made up of so many skillful musicians as that orchestra of a hundred players that Mr. Stoeckel got together from Boston and from the New York Metropolitan Opera. For example, in The Oceanides I achieved a build-up that, to a very great degree, surprised even myself.

The extensive work and revisions to The Oceanides produced a result that pleased Sibelius, as he wrote to his wife Aino: “[I]t’s as though I found myself, and more besides. The Fourth Symphony was the start. But in this piece there is so much more. There are passages in it that drive me crazy. Such poetry.” Carl Stoeckel later recounted the premiere:

Everyone who was fortunate enough to be in the audience agreed that it was the musical event of their lives, and after the performance of the last number there was an ovation to the composer which I have never seen equaled anywhere, the entire audience rose to their feet and shouted with enthusiasm, and probably the calmest man in the whole hall was the composer himself; he bowed repeatedly with that distinction of manner which was so typical of him … As calm as Sibelius had appeared on the stage, after his part was over he came up stairs and sank into a chair in one of the dressing rooms and was very much overcome. Some people declared that he wept. Personally, I do not think that he did, but there were tears in his eyes as he shook our hands and thanked us for what he was pleased to call the “honor we had done him”.

The water nymphs of Greek mythology receive a sympathetic depiction in Sibelius’ music — although more Baltic Sea than sunny Mediterranean. Soft undulations portray waves amidst the vast expanse of sound. Metrical regularity is subdued, giving greater emphasis to the ripples of energy that pulse through the work. The sound palette is built of myriad small crests eventually building to a massive breaker. The ocean swell dissipates and the tone poem ends calmly.

© Eric T. Williams

Gustav Mahler, “What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me”

Born into a Jewish family in Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic), Gustav Mahler was the second of 14 children. He showed musical talent at a relatively early age and began piano lessons at age 6. He was admitted to the Vienna Conservatory in 1875 and later attended Vienna University, studying music, history, and philosophy.

Known today for his monumental symphonies, Mahler was most highly regarded during his own lifetime as a conductor. He began his conducting career in 1880 with a job at a summer theater, ambitiously moving almost yearly to successively larger opera houses. From Bad Hall, he went to Ljubljana, Olomouc, Vienna, Kassel, Prague, Leipzig, and Budapest. His growing prominence led to an appointment at the Hamburg Opera in 1891, where he stayed until 1897. Converting to Catholicism to obtain the much-coveted post as director of the Vienna Opera, Mahler launched into his duties with zeal, greatly raising the artistic standards — and making enemies along the way. Mahler’s conducting duties engulfed his time during the concert season so composing was largely relegated to summers, often spent at pastoral lakeside settings.

It was in late 1901 that Mahler met Alma Schindler, a vivacious pianist and composer nearly 20 years his junior. He composed the Adagietto movement of his Fifth Symphony as a declaration of love for her. They became engaged after less than two months of courtship. They had two daughters, the eldest dying of diphtheria at age 4. Theirs was not an idyllic marriage and had as many moments of despondency as elation.

Frequently subjected to anti-Semitic attacks in the press and newly diagnosed with a heart disease, Mahler resigned from the Vienna Opera in 1907 to conduct a season at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, earning critical and popular acclaim. He returned to New York in 1910 to lead the New York Philharmonic. Falling seriously ill in February 1911, he went to Paris for an unsuccessful treatment and was then taken to Vienna where he died in May 1911 at age 50.

Mahler was well-ensconced at the Hamburg Opera when he began work on his Third Symphony during the summer of 1895. The completion of his Second Symphony — a seven-year endeavor — and its partial premiere that March undoubtedly bolstered Mahler’s confidence and he entered his next symphonic work with verve. He crafted a scenario to guide his work but it underwent seven revisions during the two years it took him to compose the symphony. The overall concept was one of how aspects of the world and life were revealed to him. One of his early outlines:

THE HAPPY LIFE

A SUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM

(Not after Shakespeare. Critics and Shakespeare scholars please note.)

- Summer marches in (Fanfare and lively march) (Introduction) (Wind only with concerted double-basses).

- What the forest tells me (1. Movement).

- What love tells me (Adagio).

- What the twilight tells me (Scherzo) (Strings only).

- What the flowers in the meadow tell me (Minuet).

- What the cuckoo tells me (Scherzo).

- What the child tells me.

Mahler also was influenced by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and two of his books: Meine fröhliche Wissenschaft (The Happy Science ) and Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spake Zarathustra ). Yet another element in the creative miasma was the folk poetry collection in which Mahler found so much inspiration, Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn). He incorporated material from several Wunderhorn songs in the symphony, including “Ablösung im Sommer” (Relief in Summer), dating from 1890, and “Das himmlische Leben” (Life in Heaven), dating from 1892.

Enjoying the seclusion of his summer residence in Steinbach am Attersee, near Salzburg, Austria, and with his sister Justine and violinist/violist friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner to manage the household, Mahler began composing what would turn out to be the second movement of the symphony. With a burst of creative energy, he would complete movements two through six that summer. He recognized the experimental path he was taking, later describing the work in a letter to Bauer-Lechner:

It is really inadequate for me to call [the Third] a symphony, for in no respect does it retain the traditional form. But to write a symphony means, to me, to construct a world with all the tools of the available technique. The ever-new and ever-changing content determines its own form. In this sense, I must always learn anew to create new means of expression for myself, even though (as I feel I can say myself) I have complete technical mastery…

Ideas percolated during the ensuing opera season and in the summer of 1896, Mahler returned to the symphony. He discarded the planned seventh movement (which found its way into his Fourth Symphony) and instead composed a massive first movement lasting more than half-an-hour, longer than many entire 19th-century symphonies. (Perhaps recognizing the demands on listeners as well as performers, Mahler called for a long pause after the first movement.) He completed the symphony that August but continued to make revisions over the next three years.

Portions of the symphony premiered over the next few years, with Arthur Nikisch conducting the Berlin Philharmonic performing the second movement on November 9, 1896. Additional performances of the second movement took place in Leipzig and Budapest in 1896 and 1897. The path for the premiere of the entire symphony would come through performances of his Second and Fourth symphonies in 1900 and 1901, respectively. The composer Richard Strauss heard both and responded kindly to Mahler’s suggestion that Strauss conduct the premiere of the Third Symphony. Scheduling difficulties arose and Strauss, as president of the Allgemeine Deutscher Musikverein (General German Music Association), arranged for the first full performance of the Third Symphony at a festival in Krefeld with Mahler conducting the premiere on June 9, 1902.

Although Mahler had written and revised the symphony’s subtitles numerous times, he expressed his ambivalence toward them in a letter to conductor Josef Krug-Waldsee around 1902.

Those titles were an attempt on my part to provide non-musicians with something to hold onto and with the sign post for the intellectual, or better the expressive content of the various movements and for the relationship to each other into the hole. That it didn’t work (as in fact it could never work) and that it led only to misinterpretations of the most horrendous sort became painfully clear all too quickly. It was the same disaster that had overtaken me on previous and similar occasions, and now I have, once and for all, given up on commenting, analyzing, and all such experiences of whatever sort. Those titles… will surely say something to you after you know the score. You will draw imitations from them about how I imagined the study intensification of feelings, from the indistinct, unyielding, elemental existences (of the forces of nature) to the tender formation of the human heart, which in turn points toward and reaches reach and beyond itself (God).

Irrespective of this attitude to subtitles, Mahler described the symphony’s second movement as:

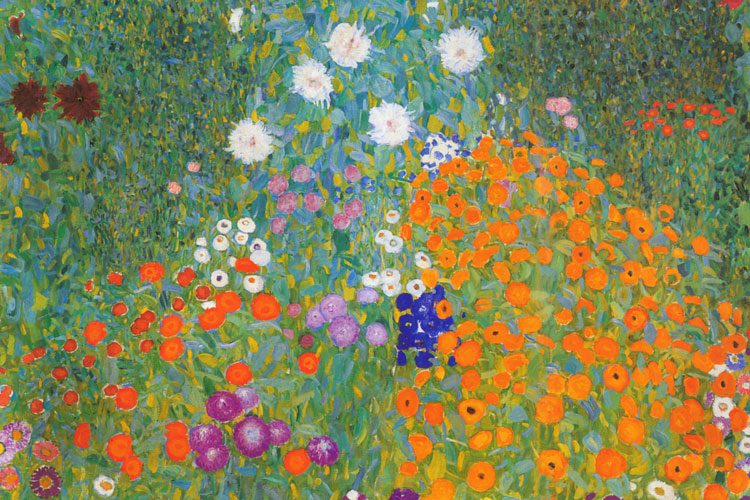

…the most carefree music I have ever written, as carefree as only flowers can be. It all sways and ripples like flowers on limber stems sway in the wind…That this innocent flowery cheerfulness does not last but suddenly becomes serious and weighty, you can well imagine. A heavy storm sweeps across the meadow and shakes the flowers and leaves. They groan and whimper, as if pleading for redemption to a higher realm.

… Rather than a continual development of the same sequence of notes, mine are decorative variations, arabesques, and garlands woven around the theme.

Marked as a graceful minuet (with the imperative not to rush!), the movement begins with the oboe delicately singing the melody. Mahler immediately embarks on variations that swirl delightfully before being engulfed by a moment of frenetic activity, soon calmed by the return of the refined minuet. He repeats this stormy pattern to great effect and the movement ends tranquilly (with repeated instructions not to rush and to give it time). Beautiful and carefree music, indeed!

© Eric T. Williams

Sergei Prokofiev, Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 63

Prokofiev’s first violin concerto was composed in quite different circumstances than that of the second. The first was begun in stormy 1917, the year of the cataclysmic events that initiated the Russian Revolution. It was nevertheless a year of great artistic productivity for the young composer. Among the compositions from that year familiar to audiences today are the Classical Symphony and the third piano concerto. He had by then garnered a reputation as a dedicated modernist, a composer of considerable capacity to shock with his sarcasm, motoric rhythms, adventuresome melodies, and pungent harmonies. Yet, the essentially lyric side of him was pronounced and innate. The first violin concerto is distinguished for its lyricism, almost romantic in its expression. The requisite virtuosity is there, of course. But, all in all, it is representative of the most progressive side of him.

The second violin concerto dates from some seventeen or eighteen years later, in much changed circumstances. And yet, surprisingly, the two works bear some degree of resemblance. By 1935 Prokofiev had been in contact with representatives of the Soviet government, which was trying to entice him back home with promises of nice accommodations, commissions, and a prestigious position in the world of Soviet music. To tell the truth, since the early nineteen thirties he had rethought his fundamental style of composing and had concluded that a more direct, appealing, and approachable style would bring him closer to his audiences. Voilà! Just what the Soviet artistic watchdogs had decreed as suitable for the proletariat: Socialist Realism! Music for the average guy. The two views were totally congruent, so the composer’s move back to the USSR was an easy one. The concerto was Prokofiev’s last composition before that removal, and like the first concerto, there is considerable appealing lyricism in the second work. Audiences loved them both, with the second enjoying an immediate success.

It was composed for the French violinist, Robert Soëtens, for whom he had written a previous composition, and he had composed it here and there as the two toured together just before the composer’s trip home. At the time Prokofiev was also working on the ballet, Romeo and Juliet, having finished his music for the film, Lieutenant Kije the year before. So, it should not come as any surprise that the ingratiating, almost romantic, tunefulness and lyricism of both works should be found in the second violin concerto.

The first movement begins with a dark, simple five-note theme, played by the soloist alone, in the low, rich register of the violin. Prokofiev had made reference to his goal of achieving a “new simplicity” in his style, and this is surely it. After the theme is extended a bit, the lower strings take it up. Following some spritely passagework, the second theme appears, just as lyrical as the first, but now, of course, in a major key, replete with the composer’s familiar quick tonal shifts. If you miss it, the horn takes it up right away, followed soon by the oboe. These two attractive ideas are the basis of the movement, along with the expected virtuoso figurations and a vigorous development. But it never gets too stormy and a somewhat ominous ending is signaled by the horns and pizzicato strings.

If the first movement may be said to be lyrical, the second is absolutely romantic, where is the sardonic Prokofiev that we knew so well? Accompanied by gentle pizzicato strings and soft woodwind chords, the soloist soars above them. Variations follow, with other material contributed by the woodwinds. A quicker tempo and busy figurations in the solo violin provide contrast in the movement’s central sections, and the woodwinds and brass announce the return of the opening. After recapping the way he began the movement, Prokofiev surprises us by turning the gentle ending upside down: This time, the soloist provides the soft pizzicatos, while the orchestra gets the chance to explore the appealing, sustained “romantic” tune. Everything ends pensively, with the low strings having the last word.

The last movement is a vigorous dance, but not that fast, and not that loud. And here, as in the whole concerto, Prokofiev makes creative use of the small battery of percussion (played by one person), which includes the very Spanish castanets. Perhaps that the concerto’s première was intended for Madrid was influential, here, but the Spanish influence is abstract, at best. Nevertheless, there is a swagger to the whole, aided by the syncopations and string effects that are redolent of so many concert works that evoke Spain. This attractive work, in so many surprising ways, is yet again an eloquent testimony against the foolish temptation to “pigeonhole” the musical style of superb composers. It may have been written with his removal back to the USSR close at hand, but it is in no way an example of “Soviet Realism” with the attendant simplicities and contortions of that sad totalitarian art.

© 2016 William E. Runyan

intermission

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 2, in C minor, Op. 17 “Little Russian”

Tchaikovsky composed six symphonies, all of which are played today, but the last three are decidedly the most popular. However, there is much value and enjoyment in the first three, all of which deserve to be heard more frequently. Tchaikovsky’s second symphony was composed during the summer of 1872, while the composer was vacationing in Ukraine at his sister’s country home. While in Ukraine the composer travelled around the country, and evidently encountered the region’s folksongs. That being the case, it is no surprise that many of the important tunes and themes in this symphony should be based upon native Ukrainian melodies. In fact, that is the exact rationale for one of Tchaikovsky’s friends later dubbing the work, “Little Russian.” While the symphony is not a long one, it is neither “little,” nor–the nickname notwithstanding–is it “Russian.” For centuries Russians often referred to Ukraine as Little Russia; it has long rankled Ukrainians, and current events certainly bear out that animosity today. So, even if it probably more clearly could be called Tchaikovsky’s “Ukrainian” symphony, “Little Russian” it is.

By roughly the middle of the nineteenth century, Russian composers were seeking a distinctive niche for themselves, one that reflected their own time and place. Yet, there was an equal commitment to incorporating many of the styles and forms of great European music. Tchaikovsky found himself in the middle of the debate and one can trace elements of both approaches in all of his music, but with a distinct slant to the latter. His second symphony, with its usage of folksong, is clearly the high water mark of his employment of the approaches of the nationalistic, folksong group—often called the “Russian Five”, or the “Mighty Handful.” It was given its première in January of 1873 in Moscow, and unlike the piano concerto from two years later, met with mighty approval and rave enthusiasm, especially from that group. Accolades came, as well, from the villain of the initial piano concerto reception, our friend, Nikolai Rubenstein, who conducted the first performance of the symphony.

There are a few, but charming, eccentricities in the symphony, starting right at the beginning. The slow introduction starts with a horn solo, which lays out the melancholy first theme, a Ukrainian folksong. It is taken up by various parts of the orchestra, as the introduction gradually gains in intensity and implied motion. Snatches of it will be heard again in the middle of the movement, and more completely at the end. After a brief segue in the trombones, followed by the horns, the second theme may be heard first in the clarinets. This is the material that will dominate the movement and is the chief reason some pundits like to compare it with the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5: both are in C minor, and there is some similarity between the rhythm and outline of the two composer’s respective themes. You’ll hear Tchaikovsky’s “second theme” everywhere in this movement. A bit later, there is a third theme in the woodwinds that is decidedly lyrical and less threatening characterized by a pleasant little movement upwards, but Tchaikovsky uses it sparingly and when in need of contrast. At the end of the movement, we again hear the solo horn playing as at the beginning, and the whole affair, notwithstanding the overall intensity of the movement, ends softly.

The second movement is a short one, and is not the usual slow one, rather it is a quirky little processional march that was more or less “left over” from an early, aborted opera of Tchaikovsky’s. Lightly scored, the march returns periodically after some diversions into other material, including, yes, another Ukrainian folksong. A last return of the march heralds the end, and gossamer-like, gently fades out of sight and sound. The third movement, a scherzo, partakes of much of the same “Midsummer Night’s Dream” atmosphere but is suitably vigorous. The obligatory contrasting mood in the middle, introduced by a “village band” in the woodwind section, changes the usual rhythm from three to two to a bar. A return to the opening scherzo scampers along to a conclusion that would make Berlioz proud.

The last movement starts off with a grandiose tune in the whole ensemble that many have compared with a little “Great Gate of Kiev.” It is a well-known Ukrainian folksong, “The Crane,” which legend has it was first sung to the composer by a servant in the house in which he was staying. The strings take up the tune, and this “first theme” is worked through a long series of variations that bear the inimitable hallmark of the composer’s mastery of orchestration. It’s easy to follow this vigorous dance tune as he puts both it and the orchestra through their paces. Tchaikovsky is a master of what seems to be an infinity of color combinations and rhythmic ideas. After what surely is the end, the composer finally introduces the contrasting idea, one of his own devising, heard first in the strings. It’s a graceful, nostalgic little salon tune that provides a useful foil to the ruckus of the main idea. Tchaikovsky goes on to develop them together in the ensuing section, but it’s really the boisterous “The Crane” that dominates all, here. It doesn’t take long for one to sense the inevitable Tchaikovskian steamroller to the end. It teases and builds slowly, but you know that it’s coming, as woodwinds, strings, and brass, all with their own ideas,interact in a cascade of sound. “The Crane” and the little salon tune each get their due, but after a grand pause proceeded by stentorian low brass and a tam-tam crash, the breathtaking dash to the end ensues. The excitement is an absolute peer to all the finales that we love so much from the more familiar symphonies, and makes us all the more glad that we now know this one, as well.

© 2015 William E. Runyan